An Introduction to Psilocybin (Magic Mushrooms)

What if, deep inside your mind, there are doors you’ve never even noticed — doors that have stayed quietly locked your whole life? Have you ever wondered why certain patterns of thinking feel impossible to break?

Why do some emotional wounds still ache years later, no matter how much therapy or self-help you’ve tried? Or why, in your clearest moments, have you felt a sudden flash of creativity, peace, or connection that vanished as quickly as it arrived?

What if those doors are hiding the answers — or at least the space where real healing and insight can finally happen?

And what if nature created a gentle, time-tested key that indigenous cultures have used reverently for thousands of years? A key that modern science is now rediscovering as one of the most powerful tools for mental and emotional transformation we’ve ever studied.

That key is psilocybin.

An introduction to psilocybin.

Psilocybin (pronounced "sill-oh-SY-bin") is a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain mushrooms (often called "magic mushrooms" or “shrooms”). Psilocybin is a gift from nature that's been around since the dawn of time, quietly growing in forests, fields, and even backyards across the globe.

These fungi grow wild on every continent except Antarctica.

For beginners, the most important thing to know is that Psilocybe cubensis is the safest and most widely studied “gateway” species. It is mild, forgiving, and the least likely to cause an accidental, overwhelming dose.

Animated explainer: Psilocybin mushrooms' psychoactive effects, metabolism to psilocin, 5-HT2A receptor activation, tolerance, and non-addictive safety in the brain.

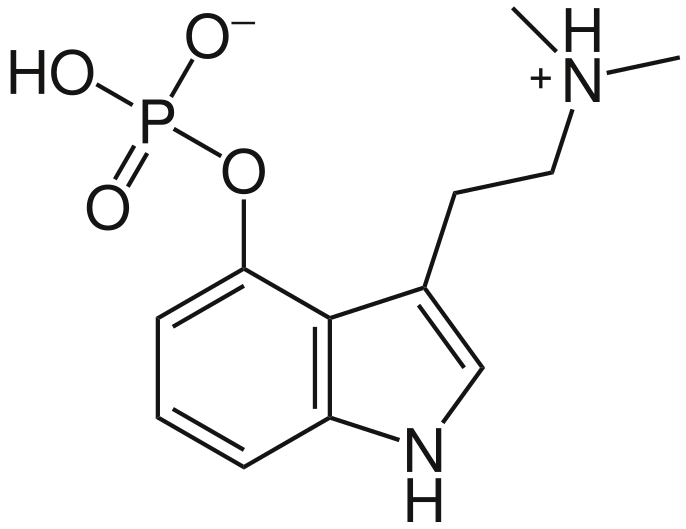

Chemistry & Molecular Structure.

Psilocybin is a tryptamine alkaloid closely related to serotonin, the primary neurotransmitter responsible for mood regulation in the brain.

Upon ingestion of the mushrooms—whether in their fresh or dried form, or prepared as a tea—the human body rapidly metabolizes psilocybin into psilocin. This conversion is significant because psilocin is the active compound that effectively traverses the blood-brain barrier, thereby inducing the psychedelic experience.

History and cultural significance.

Ancient Use: Thousands of Years Before the Term "Psychedelics" Existed:

Mushroom stones from the Maya and Olmec cultures in Mexico and Guatemala date from 1000 to 500 BCE, with some dating back 3000 years.

The Aztecs referred to psilocybin mushrooms as teonanácatl ("flesh of the gods") in the 16th-century Florentine Codex.

The Most Famous Modern Rediscovery: María Sabina (1950s):

1955: R. Gordon Wasson joined a velada with the Mazatec curandera María Sabina.

1957: Wasson's article "Seeking the Magic Mushroom" was published in LIFE magazine, marking the first major exposure to the subject in the Western world.

Western Science Enters the Picture:

In 1958, Albert Hofmann at Sandoz Laboratories isolated psilocybin and psilocin from samples sent by Wasson and synthesized both compounds.

Sandoz marketed synthetic psilocybin as Indocybin for psychiatric research from 1959 to 1965.

The 1960s Boom and the Backlash:

From 1960 to 1963, Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) conducted the Harvard Psilocybin Project.

The Harvard Psilocybin Project was shut down due to controversy, and psilocybin was placed under strict control, eventually becoming a Schedule I substance in the U.S. in 1970.

50 Years in the Shadows (1970–2000):

Almost all human research was suspended worldwide after the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

The Modern Renaissance (2000–2025):

In 2006, the first modern FDA-approved study on psilocybin was conducted at Johns Hopkins University (Griffiths et al.).

In 2020, Oregon voters approved Measure 109, leading to the opening of the first licensed psilocybin service centers between 2023 and 2024.

In 2022, Colorado voters passed Proposition 122, which allowed for regulated access that began in late 2024.

By 2025, Australia, several provinces in Canada, and the Netherlands will permit the therapeutic use of psilocybin under medical frameworks.

Cultural Significance Today:

Books such as Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind (2018) and the 2022 Netflix docu-series of the same name have become massive bestsellers, bringing psilocybin into mainstream discussion. Podcasts featuring hosts like Tim Ferriss, Joe Rogan, and Aubrey Marcus regularly include researchers and therapists, normalizing the conversation around psilocybin for millions of listeners.

By 2025, psilocybin will no longer be considered “fringe.” It can be found on bookstore shelves, in therapy offices, and in state laws. However, the cultural conversation has evolved: most thoughtful voices now agree that respecting the Indigenous origins of psilocybin is essential. This understanding serves as the foundation for using this medicine responsibly in the modern world.

How psilocybin works in the brain, common effects, and experiences.

Time After Ingestion: 0-30 Minutes (Come up-Up).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Psilocybin → Psilocin conversion.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Psilocybin has difficulty crossing the blood-brain barrier. However, enzymes, mainly alkaline phosphatases found in the gut and liver, quickly remove the phosphate group, converting it into psilocin. Blood levels of psilocin begin to rise sharply around 20 to 40 minutes after ingestion.

What You Might Notice: You may experience slight nausea, which is a common part of the "come-up" body load, as well as feelings of anxiety or excitement. You might also notice mild yawning and dilation of the pupils.

Time After Ingestion: 30-90 Minutes (Peak Onset).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Peak 5-HT₂A receptor activation. The Default Mode Network (DMN) ↓. Brain entropy dramatically ↑.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Psilocin strongly activates serotonin receptors, quiets the “ego network” (Default Mode Network), and creates new temporary connections across the brain.

What You Might Notice: The “whoa” moment: visuals begin (breathing walls, patterns), time distortion, emotional amplification, and ego boundaries start to soften. Peak intensity typically occurs between 60 and 90 minutes.

Time After Ingestion: 90 Minutes-2 Hours (Deep Immersion).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Maximum breakdown of usual brain hierarchies.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Thalamus gating relaxes, leading to a sensory flood and the formation of new, temporary connections between normally segregated networks, such as the visual and emotional/memory networks.

What You Might Notice: Intense visuals, synesthesia, mystical experiences, and ego dissolution.

Time After Ingestion: 2-4 Hours (Plateau/Descent).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Cross-talk continues, intensity declines.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Psilocin plasma levels are decreasing; the liver metabolizes through MAO and glucuronidation; neural networks remain hyperconnected.

What You Might Notice: The peak has passed; experiences become more reflective and gentle, involving deep emotional processing, laughter, tears, or quiet awe. Many people feel they can better “steer” the trip now.

Time After Ingestion: 4-6 Hours (Return & Reflection Phase).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Effects fade as psilocin is cleared.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Psilocin levels fall below the threshold for strong 5-HT₂A activation, allowing brain activity to gradually return to baseline patterns.

What You Might Notice: “Afterglow” begins with feelings of euphoria, clarity, tiredness, or mild confusion. Most visuals fade away, and you feel more “back in your body.”

Time After Ingestion: 6-24 Hours (Afterglow).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Acute afterglow & early neuroplastic window.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Serotonin receptors begin to upregulate again, leading to increased levels of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) and other growth factors within hours. This initiates a period of heightened neuroplasticity.

What You Might Notice: Classic afterglow: an elevated mood, brighter colors, a sense of gratitude, and a renewed perspective. Sleep is often deep and refreshing.

Time After Ingestion: Days to Months later (Integration Period).

What Happens in the Body and Brain: Lasting neuroplasticity.

Detailed Neurological Explanation: Increased dendritic spine density and sustained changes in DMN connectivity in responders.

What You Might Notice: Consistent improvements in mood, openness, and cognitive flexibility.

Potential benefits and therapeutic uses of psilocybin.

Clinical trials now show psilocybin-assisted therapy (1–2 guided sessions) can produce rapid, lasting relief for:

Treatment-resistant and major depression (60–80 % significant improvement lasting 6–12+ months, often outperforming SSRIs).

End-of-life anxiety in cancer patients (single dose → profound, sustained reductions).

Addiction (80 % smoking cessation at 6 months — the best result ever recorded; strong results for alcohol and emerging data for opioids/cocaine).

Early promise for PTSD, OCD, and cluster headaches.

Healthy volunteers frequently report increased openness, life satisfaction, and a lasting connection to nature. The combination of a profound personal experience and a “reset” of stuck brain networks explains why benefits are often so durable.

Risk, side effects, and safety concerns when using psilocybin.

Psilocybin is one of the safest psychoactive substances regarding physical toxicity. There have been no confirmed overdose deaths from psilocybin alone; it has an extremely low potential for addiction, and its lethal dose is estimated to be thousands of times greater than a typical recreational amount.

Common Acute Side Effects (usually resolve within hours):

Nausea and vomiting are very common, especially during the come-up.

Headaches, dizziness, and transiently elevated blood pressure and heart rate can also occur.

Additionally, feelings of anxiety, paranoia, or confusion may arise during the experience.

Psychological Risks:

Challenging experiences during trips can involve intense fear, paranoia, or temporary psychosis-like states. These risks are most common with unsupervised use and are rare in guided settings.

Additionally, such experiences can trigger or worsen mental health issues in individuals with a personal or family history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe anxiety. Strict screening processes are used to exclude these individuals in clinical trials.

There have also been rare cases of increased thoughts of suicide or suicidal behavior following sessions, particularly observed in some depression trials.

Rare Long-Term Concerns:

Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) involves visual "flashbacks" or disturbances, such as snow, trails, and halos, lasting from weeks to years. It affects fewer than 5% of users and is often mild or benign.

Flashbacks, which are brief re-experiencing episodes, are common but typically not distressing.

Other Important Safety Issues:

Mushroom misidentification → Accidental poisoning by toxic look-alikes (liver/kidney failure possible).

Mixing with other substances (alcohol, stimulants, antidepressants) → Increases risk of bad trips or serotonin syndrome.

Cardiovascular strain → Caution if pre-existing heart conditions

Legal risks → Still Schedule I federally in the U.S. (illegal outside research/Oregon/Colorado programs).

Key Takeaway:

In controlled clinical settings that include screening, preparation, and support, serious adverse events related to psilocybin are rare, and there have been no reported deaths attributed to its use. However, unsupervised recreational use poses greater psychological risks, particularly for vulnerable individuals. It is essential to prioritize three key factors: mindset (your mental state), setting (a safe environment), and harm reduction practices.

Dosage, Preparation, Set & Setting.

Psilocybin dosages are usually measured in two ways: either in dried mushrooms, which is the most common method for natural sources, or in pure psilocybin, which is often used in clinical trials. For dried Psilocybe cubensis, the most widely used species, the dosage categories are as follows:

- Microdose: 0.05 to 0.3 grams.

- Low/Museum dose: 0.5 to 1.5 grams.

- Moderate/Therapeutic dose: 1.5 to 3 grams (approximately 15 to 30 milligrams of pure psilocybin).

- High/Heroic dose: above 3.5 to 5 grams (at least 35 milligrams of pure psilocybin).

These classifications help users understand the different effects and purposes of various dosages.

Preparation significantly impacts the experience. Fasting for 3 to 4 hours or consuming only a light meal can help reduce nausea. Many people make tea or use the "lemon tek" method, which involves soaking ground mushrooms in citrus juice for 15 to 20 minutes. This method can help speed up the onset, shorten the duration, and lessen nausea. It is also recommended to have water, light snacks, and 12 hours of calm afterward.

Set and setting are the most essential safety factors and dramatically affect the outcome.

Set refers to a mindset—approaching the experience with clear intention and emotional stability, without acute life crises. Individuals with a personal or family history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe anxiety are generally advised to avoid psilocybin.

The setting refers to the physical and social environment in which an experience takes place. An ideal setting is a quiet, comfortable, and familiar space, equipped with soft lighting, blankets, and a carefully selected music playlist.

For doses exceeding 1.5 grams, it is highly recommended to have a trusted, sober sitter or guide present. Clinical trials indicate that proper psychological support significantly reduces the likelihood of challenging experiences, decreasing the rate from approximately 30% (without supervision) to under 5%.

Beginner's guide video: Psilocybin mushroom dosing, set & setting, therapeutic benefits for anxiety/depression, and safe preparation tips.

Myths and Misconceptions.

“It’s highly addictive.” False. Psilocybin has one of the lowest abuse potentials of any psychoactive substance; no physical dependence, almost no cravings.

“You can overdose and die.” Practically impossible. The lethal dose is thousands of times higher than a strong recreational dose; there have been no confirmed deaths from psilocybin alone.

“It causes permanent insanity.” Large population studies and modern trials show no link in healthy, screened people. Risk exists only for those with a history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

“It fries your brain.” The opposite: it promotes new brain connections and plasticity.

“Flashbacks/HPPD are common and terrifying.” They affect <5 % of users and are usually mild and temporary.

Most fears come from 1960s propaganda, not evidence.

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XBEas8MGzd0

https://recovered.org/hallucinogens/psilocybin/psilocybin-legal-status

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8901077/

https://www.science.org/content/article/ancient-mesoamerican-mushroom-stones

Florentine Codex, Book 11 (Sahagún, 1577)

LIFE magazine, May 13, 1957

Hofmann, A. (1958). Experientia paper

Sandoz Indocybin brochure (archived)

https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2012/01/the-harvard-psychedelic-club

Controlled Substances Act of 1970

UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances 1971

Griffiths et al., Psychopharmacology (2006)

Oregon Psilocybin Services (oregon.gov)

Colorado Natural Medicine Health Act

TGA Australia rescheduling July 2023

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-003-1683-1

https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn2884

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1119598109

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020/full

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aat0094

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2014.0873

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00094

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-019-0500-8

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(18)30755-1

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.adf2820

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04554-7

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2783812

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2032994

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/article-abstract/2791840

https://compasspathways.com/our-research/psilocybin-therapy/comp360-psilocybin-treatment/

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269881116675513

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269881116675512

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269881114565148

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2794693

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (search NCT05265442, etc.)

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269881116675514

https://www.nature.com/articles/npp201784

https://erowid.org/plants/mushrooms/mushrooms_dose.shtml

https://thethirdwave.co/psilocybin-dosage-guide/

https://zendoproject.org/resources/psychedelic-harm-reduction/

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/psychiatry/research/psychedelics-research

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269881116653108

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61462-6/abstract

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0063972

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(18)30755-1

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12652822/

Beug et al. – Mushroom poisoning statistics (annual reports)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-021-01069-x

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkETlKOERlk